El Greco's Spain

Travelers should be predisposed to like Doménikos Theotokópoulos. His popular name, El Greco (The Greek), came from the fact that he spent most of his life as an ex-pat. He left his homeland in his twenties, completely reimagined his personal style in Italy, and settled down as a master of his craft in Spain. As a traveler and an artist, I appreciate how each place El Greco lived left its mark on his artwork – and yet, he managed to develop a style so unique and personal that today he is recognized as a visionary, years ahead of his time.

El Greco was born in 1541, on the Greek island of Crete. At the time, Crete was an overseas colony of the Republic of Venice and had become important in the world of religious icon painting. Orthodox artists in the east created highly stylized and decorative works, with jewel-like colors and gold embellishments. Catholic artists in the west were starting to focus on realism, especially in the background landscapes and overall composition of their works. The artists on Crete combined the two schools and created the post-Byzantine style, continuing to use the bold color palette of Byzantine art with more naturalistic, western-inspired backgrounds and figures.

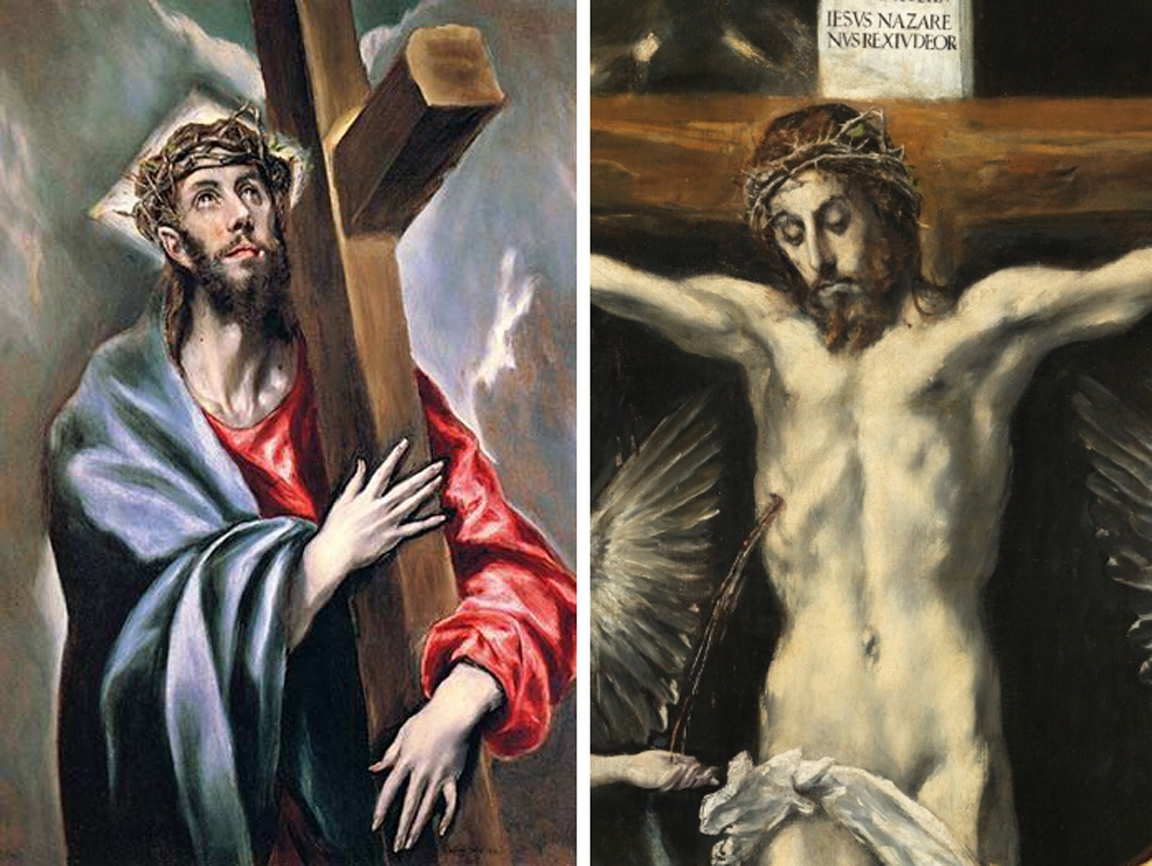

I started my trip to Spain with a layover in New York, during which I visited the Met. While there, I took my time looking at El Greco’s beautiful painting of Christ Carrying the Cross, noting the distinctive shape of the crown of thorns. It's a composition the artist would repeat at least seven times - there are versions in Madrid, Barcelona, Buenos Aires, and London - though the Met's version is probably the finest. In his best painting, El Greco's elongated figures seem other-worldly - a thin veil of flesh barely containing the light that seems to glow out of the figures. The fabric that swirls around them seems ready to ascend to the heavens with their bodies at any moment. The loose brushstrokes add a sense of urgency, while the strong highlights recall the artist's roots as an icon painter.

El Greco established himself as a master icon painter in his homeland before traveling to Venice at the age of 26. A half-century earlier, Venice had undergone a golden age in art – the Venetian school included painters such as Bellini, Giorgione, Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese. Given the city's beautiful light, Venetian art focused on color rather than line. Many Cretan artists traveled to Venice, but most returned home with a few new tricks, their style largely unaltered. However, in Venice, El Greco’s work began to undergo dramatic changes. He embraced the style of light, color, composition, and form created by Venetian artists, Titian and Tintoretto in particular.

A few years later, El Greco moved on to Rome. While in Rome, he added the dramatic poses and more structural compositions found in Mannerist works to his own. He also established himself as someone with fierce opinions, even about the masters like Raphael and Michelangelo (he wasn’t a fan of the latter’s sense of light and color), which earned him some derision in the artistic community. Still, he was recognized as having great talent, and set up his own workshop in Rome.

In 1577, El Greco moved to Spain, first seeking patronage in the royal court of Madrid. El Escorial had just been built, King Philip II’s favorite artist (Navarette) had recently died, and El Greco was hoping to use his Roman contacts to secure him a royal commission. He received one to paint The Martyrdom of Saint Maurice. Philip wasn’t a fan – El Greco had chosen an unusual moment of the saint’s story to depict, with the actual martyrdom happening off to one side. The composition also took on a sense of religious mystical fervor would have made a staunch inquisition-era Catholic slightly uncomfortable. The painting was too out-of-the-box and personal for the Spanish king. Phillip had it placed in a side room rather than its intended altar and never offered El Greco a commission again.

At roughly the same time as the royal commission, El Greco worked on a commission for the Cathedral of Toledo. The Disrobing of Christ was to become his first masterpiece –in Toledo, El Greco finally found the favor and fame he’d been seeking all his life. Toledo was the center of religious art – and religion, in general –in Spain at the time. Stylistically, it was still the city of three faiths, with inspiration from Christian, Jewish, and Islamic art. Because of this, Toledo was slightly more open to religion with a mystical bent, which both suited and continued to form El Greco’s style. He started a studio in 1685 and in 1686, painted his best-known work, The Burial of Count Orgaz, for his own parish church.

Interestingly enough, visiting the work that was a failure - Saint Maurice - in El Escorial was a far more rewarding experience than seeing the Burial of Count Orgaz in Toledo. The tiny Iglesia de Santo Tomé in Toledo was jam-packed with tourists when I went. Each group shuffled forward, spent about two minutes in front of the painting, then left with their guide. Not being on a tour, I lingered a bit, enjoying the incredibly painted men of Toledo who contrasted so well with the glowing chaos of the heavens above. Still, it was a less than ideal setting, whereas the work in El Escorial was in an almost-empty, quiet room, in which I really had time to enjoy the glowing colors and ethereal forms on the canvas in front of me.

A better experience was to be found at the El Greco Museum in Toledo. Given his massive output of work, and the audience he found for it in Toledo, El Greco was quite well off in the prime of his life. He was the tenant of a 24-room apartment complex owned by the Marquis de Villena. While this building no longer exists, a house from the same era is used to recreate the artist's living space. The museum was revamped a few years ago. It's located in the Jewish quarter of the city, downhill from and to the west of the cathedral.

After entering the modern ticket office, you're free to wander the garden or explore the cave-like cellars on the property before entering the old building. The central courtyard is flanked by a recreation of a kitchen, along with other rooms, art sprinkled here and there. After passing through the upstairs, you enter the modern museum wing, where you'll find the finest of several sets of portraits of Christ and his 12 Apostles that El Greco painted.

You’ll come across works by El Greco in pretty much every art museum in Madrid – on my first day exploring, I found some at the Museo Cerralbo, the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando, and the Thyssen Bornemisza. El Greco was incredibly prolific – true to his origins as an icon painter, he would paint the same composition again and again to fulfill commissions. He and his workshop created over 100 representations of Saint Francis alone.

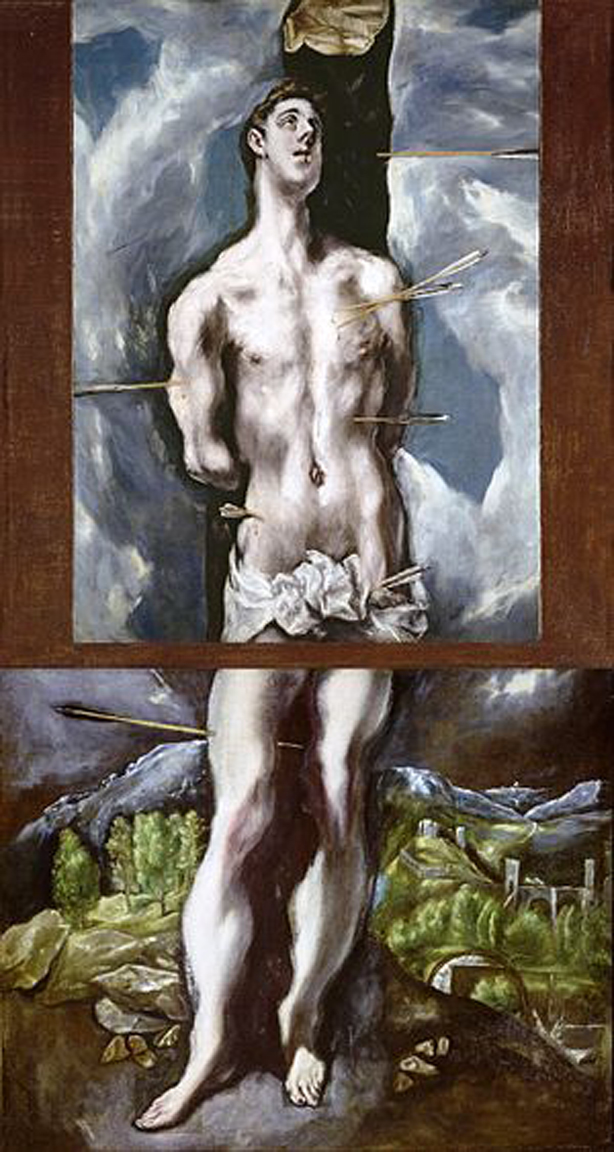

The Prado has 42 works by El Greco and his studio. Some are portraits of his contemporaries, while others are paintings of saints or religious scenes created for church altars around Spain. While I enjoyed seeing them all, there were two subjects in particular that caught my eye. The first was Saint Sebastian - my favorite saint, from a purely artistic standpoint. Artists from the Renaissance onward loved to depict him, as the most famous part of his martyrdom involved being stripped down and shot full of arrows by his (former) Roman comrades in arms. Basically, it was a religious excuse to paint a mostly naked man in an interesting pose. This particular Saint Sebastian is staring beatifically toward the swirling heavens. The brushwork and his elongated but muscular form are pure El Greco. Behind the saint's legs is a scene that looks an awful lot like the artist's famous scene of Toledo. The painting itself was cut down at one point and has been semi-restored in a way I've never really seen before.

The second, of course, was to satisfy my own curiosity. I had a theory from looking at the work at the Met - that El Greco probably had a physical thorn crown that he used for reference. The bends and breaks in it are just so distinctive! After seeing the pictures at the Prado, I'm not 100% sure my assumption is correct - he may have painted the rest from one, original picture rather than a physical prop - but every single crown of thorns El Greco painted has that same break on the right hand side and a similar pattern of overlap on the left.

I encountered one last version of Christ with the Cross in Cuenca. It was a pleasant surprise - with few sites in the town, I'd gone ahead and bought the combination cathedral ticket that also gave me access to the bell towers and the treasury. I'd almost forgotten about the treasury, but had a little time to kill before the Portugal game, so went inside. It was a neat and eclectic collection of religious art.

Unlike every museum I visited in Spain, there wasn't a guard sitting in each room. As I headed downstairs, I noticed that the next few rooms I'd be stepping into were within a vault, which piqued my interest. The first room had some gold and gems that would've felt at home in the Met's Heavenly Bodies exhibit. But as I stepped into the next room and saw its contents, I was filled with joy. Two El Greco paintings hung on the walls - encased with glass, but unguarded. I was the only person in the room. I took my sweet time and studied every little detail and brushstroke.

It was a lovely way to end my El Greco quest in Spain. El Greco himself only came back into vogue within the last 200 years. Following his death, the Baroque and Rococo periods overtook Europe. El Greco was thought of as crazy, gauche, a Greek disciple of Titian. It wasn't until the Romantic sensibilities of the late 19th and early 20th century that his work was reconsidered and Spain began to claim him as a Spaniard. His influence can be seen in the works of Dali and Picasso, and some critics consider him the first modern artist for constantly following his own stylistic sensibilities, as opposed to the most popular trends of the day.

Comments

Post a Comment